Do you know the moment, when someone you really trusted and looked up to, turns out to be not quite what you expected? When your deepest hopes for the future are shaken up and challenged and you’re told that no, that’s not the real story at all? You have the plans sorted out, the dreams in place, all resting on that one person and – bam! – they’re in pieces. Perhaps it’s a relationship that isn’t going where you hoped. Perhaps it’s a colleague who suddenly turns out to be untrustworthy. Or perhaps your political party elects a leader at odds with everything you’ve been working for, all these years – and yet isn’t. There are a good few people in that position in the Labour Party today.

And yet, when you look, perhaps you should have seen the signs. Your partner had been acting a bit strange lately. Your colleague had been keeping odd hours. And Labour – well they kind of knew they needed a big change. But these things are easier to see in hindsight.

And it’s even tougher when the unexpected change is something that starts from the same place as you were expecting, but goes somewhere quite different in the end.

So to the disciples and Jesus. Peter has no problem in giving his answer as to who Jesus is: he’s the Messiah. And it’s then that Jesus does two unexpected things, that shake up the worldview of Peter and the other disciples completely.

First of all, he tells Peter to shut up – this is not the time or the place. He had a point – Caesaera Philippi wasn’t the place for such a conversation, as we’ll see later. But then he goes on to completely contradict everything that the disciples thought the word Messiah meant.

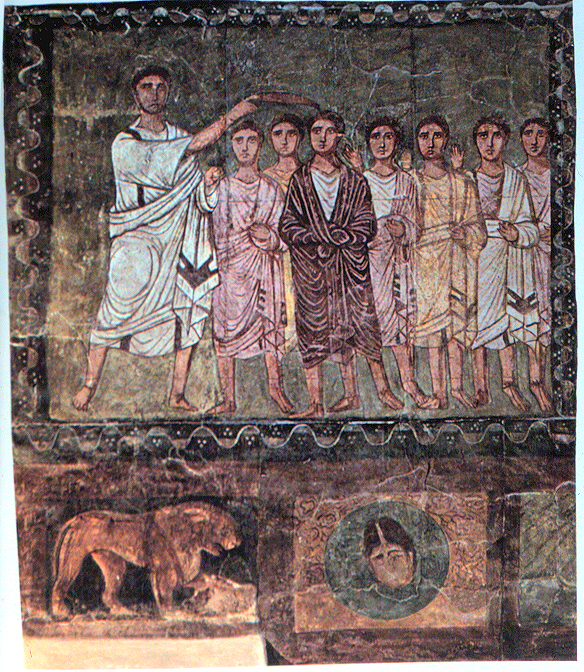

The word simply means ‘anointed one’. It relates to the ancient Jewish practice of anointing kings – this is Samuel anointing David as king, a practice that was still followed in this country when the present queen was crowned. It’s a setting-aside of the king, a marker of their acceptance by God. A Messiah is a king.

But of course Israel had not had a king for generations – it had been under one sort of foreign rule or another for a long time. So the kind of kingship that the word Messiah denoted in Jesus’ day was a liberator, and specifically a liberator through war and violence. Some Jews believed in Jesus’ day that this liberation would come here and now, others that it would come at the end of the world. Jews today still mostly believe the Messiah will come at one or another of those times.

Jesus didn’t deny Peter’s statement that he was the Messiah, but he had a very different story to tell about what it meant to be a Messiah. It involved sacrifice and suffering. It involved being rejected by the religious and political establishment. And it involved his death.

Jesus didn’t deny Peter’s statement that he was the Messiah, but he had a very different story to tell about what it meant to be a Messiah. It involved sacrifice and suffering. It involved being rejected by the religious and political establishment. And it involved his death. Now it’s important to realise that this is still a vision of Messiahship. Jesus was not saying “I’m not the Messiah, you’re wrong”. He was saying “yes I’m the Messiah, but you’ve misunderstood what it is to be the Messiah”. Jesus did come to be a king, but a different sort of king, of a different sort of kingdom as well – a richer life, full of joy and wisdom and harmony with God and full of justice to others. He called this the kingdom of God, and much of Jesus’ teaching was designed to show people the way to this kingdom, not as something to have after death, but as something to be lived now. He talked about it through stories and metaphors rather than directly, but he showed them the way to find it – to become fully awake, as some have put it. But because that kingdom involved serving others, at the deepest possible level, part of the work Jesus needed to do to help others reach the kingdom of God, was to suffer, to be condemned and ultimately to die. And that was the message Jesus told his disciples. That was what it meant to be the Messiah.

And that’s where Peter snapped. We’re only told in the gospel that Peter “took him aside and began to rebuke him” but you can imagine the conversation. “For pity’s sake, Jesus. We’ve followed you all this way since Galilee. We’ve left behind our jobs and our families and our lives, because we thought you were the real deal. We thought you were the one to save Israel, to ride into Jerusalem in victory. And now what? You’re going to get yourself on trial and killed? Come on, man, snap out of it. You could be a great leader. The people love you. They flock to hear you preach. They’re talking in all the synagogues about your miracles. Give up on this martyrdom stuff. Get out there and lead us to victory!”

It must have been tempting for Jesus. It sounds like a nice life. Uncertain, yes. But exciting too. Who out of all of us hasn’t been tempted when the voice offering us worldly power comes calling, saying we can do this thing if only we give up what we know is right? But of course Jesus had already met this kind of temptation in the desert at the start of his ministry. Yes, Peter spoke out of love and belief in Jesus’ mission. But ultimately his was the voice of temptation, the voice of Satan.

So Jesus called together the crowd to give them the implications of his being the Messiah. And now it’s worth briefly pointing out where all this conversation was taking place. Caesaera Philippi was not a safe place. It was right up in the far north of the traditional land of Israel, near the source of the river Jordan. It’s still a dangerous area, at the border of Israel and Syria in the disputed Golan Heights. It was a place where religion and power came together – there had been an ancient temple to Baal there, then an even bigger one to the Greek god Pan, then a still bigger one to the biggest god of them all in those days – Augustus Caesar. To say there that you’re the Messiah was a really dangerous act. And to do so in a way that challenged everyone’s expectations even more dangerous.

So Jesus understood the danger he was in. And he now started to lay it on thick to those listening – they were in the same danger too. By choosing to be his followers, they literally had to follow the same path as him. The way that would lead to the cross.

Now everyone learning to preach from the scripture is taught that the basic elements of a sermon are to explain the context of the passage, and to help listeners relate it to their own lives. Sometimes that’s quite difficult work, to tease out implications and meanings of some cryptic passage. But here Jesus is so plain, so upfront, that the implications for our own lives are clear. And really really scary. Jesus puts it straight: “Whoever wants to be my disciple must deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me. For whoever wants to save their life will lose it, but whoever loses their life for me and for the gospel will save it.”

The natural reaction to these verses is to shy away from them, to look for wiggle room, to try to find a way out. But there’s barely any wiggle room here. The theologian Tom Wright puts it clearly in one of his commentaries, “Jesus is not leading us on a pleasant afternoon hike, but on a walk into danger and risk. Or did we suppose that the kingdom of God would mean merely a few minor adjustments in our ordinary lives?”

I believe that this is something laid upon us whether we are lifelong Christians or new to the faith, whether we are aged 9 or aged 90. To be a follower of Jesus is to set down the things of the world, the things that make us comfortable, the things that makes life easy. To be a follower of Jesus is to be willing to embrace suffering and to embrace sacrifice.

This is not an easy calling. But it’s not one that involves hair-shirts and self-denial in the purely material sense, though it might involve those. It’s not about Puritanism, cancelling Christmas and parties. To quote an American blogger on this passage, David Lose:

We all too often view Jesus’ language of cross-bearing and denial through the lens of Weight Watchers. You know, have a little less of the things you like, don’t over indulge in the things that make you happy, cut enjoyment calories whenever possible because they’re not finally, I don’t know, Christian.But taking up one’s cross is more radical than that. In the world of 1st century Palestine, the cross was the worst possible death imaginable. It was the death given to traitors and slaves. It was deliberately humiliating, slow and drawn-out. For Jesus to draw any sort of connection with the cross must have been a shocking thing for his to hear. I said earlier that Jesus was denying that he was the kind of Messiah who would be riding into Jerusalem on a war-horse. We know that when he did finally ride into Jerusalem it was on a donkey. But Jesus was very clearly saying that as a follower of his, you’d be going up against the authorities, and you’d be in personal physical danger.

Some followers of Jesus have done just this. I’ve been privileged to hear some of them talk – the liberation theologians of the Philippines who worked out of Christian conscience to undermine the Marcos regime; the anti-apartheid campaigners in South Africa who lost their liberty in the face of that evil system; the protestors against Trident in this country who have sailed boats in the face of submarines armed with weapons of mass destruction or cut the wire of the Faslane base to plant flowers on it. I couldn’t do those things myself, but I’m convinced that they were taking up their cross.

Some followers of Jesus have done just this. I’ve been privileged to hear some of them talk – the liberation theologians of the Philippines who worked out of Christian conscience to undermine the Marcos regime; the anti-apartheid campaigners in South Africa who lost their liberty in the face of that evil system; the protestors against Trident in this country who have sailed boats in the face of submarines armed with weapons of mass destruction or cut the wire of the Faslane base to plant flowers on it. I couldn’t do those things myself, but I’m convinced that they were taking up their cross. Yesterday afternoon as I was preparing this sermon, I read a message on Twitter, written by an American Christian activist for social justice called Craig Greenfield, who has lived most of the past 15 years in the slums of Cambodian. He writes: “Laying down your life usually doesn't happen in a blaze of glory. But rather in tiny moments of anonymous choice that you face every day.”

We can’t all cut the wire at Faslane or move to the slums of Cambodia. But we can all ask ourselves: what are we willing to risk as a follower of Jesus? What part of our lives are we prepared to lay down as his followers? What does it mean for us to take up our cross and follow him?

And Jesus offers us a mighty promise – that by doing so, we cast aside the rubbish that entangles so many of us. We get rid of the material clutter, of the hurts we cause others, of the lack of care we show to our fellow human beings. We die in Christ, and we are reborn in Christ. We are enabled to wake up to the kingdom of God, to live in the full richness of that life which he came to show us. We are enabled to live out our life abundantly and richly and so much more fully than our old lives. He promises it to us all: take up your cross, follow me, and you will gain life in all its fullness.

Amen.

No comments:

Post a Comment